Bridges

Context

Before the Industrial Revolution, rural communities were usually fairly self-sufficient and journeys were predominantly local. A weekly trip to the nearest market could be accomplished on foot or horseback or, if necessary, by horse and cart. Longer journeys driving livestock to cities were usually made on long-established drove roads by professional drovers. As a consequence, most roads were little better than the footpaths we are familiar with today – beaten tracks flattened by centuries of footfall. Winter use was difficult and sometimes perilous. Parishes had the responsibility of their maintenance and this would normally have meant filling-in potholes with stones, the cost being met from local tithes and the labour being provided free-of-charge by local residents. The system of compacting small stones into a hard surface, invented by the Scottish engineer John McAdam, was not introduced until the 1820s.

More often than not, rivers and streams were crossed by fords, ferries and rudimentary timber bridges. The Rev. J. Evans (‘Late of Jesus College, Oxon.’) wrote in his A Tour Through Part Of North Wales in the year 1798… that Llanidlos (sic) ‘..has a very old wooden bridge over the Severn, at present in a very decayed state, and which is only used in times of flood; at others the river is fordable.’ The Rev. W. Bingley (Fellow of the Linnean Society and late of Peterhouse, Cambridge) wrote about his ‘excursions through all the interesting parts’ of North Wales during the summers of 1798 and 1801. One excursion took him from Welsh Pool (sic) to Oswestry, by way of Llanymynech. ‘Just before I arrived at Llanymynech, I had to cross the furious little river Virnwy by a ferry’, he wrote. In later years, both the Severn at Llanidloes and the Vyrnwy at Llanymynech were to be crossed by bridges designed by Thomas Penson.

There were, of course, some much earlier stone-built bridges. ‘Clapper’ bridges were the simplest kind: a series of large boulders with flat slabs placed across them. Packhorse bridges were designed specifically to carry horses laden with panniers – narrow, with low parapets. One of the most notable of the few in Wales crosses the River Alyn at Caergwrle (Flintshire) and is thought to have been built in the 17th century. Earlier bridges still exist, though rarely. Llangollen bridge, according to Rev. J. Evans, was ‘built by John Trevor, Bishop of St. Asaph, in the year 1346, and is considered by the Welsh, as one of Tri Tlws Cymru, or, The three Elegant Things of Wales.’ Anthony Blackwall (County Bridge Engineer of Shropshire in the late 1970s) in his book ‘Historic bridges of Shropshire’, published in 1985, describes a number of early bridges, including several along the border with Wales. One, near Penybont Llanerch Emrys spans the River Cynllaith where it forms the border between Shropshire and what was then Denbighshire. He reports that ‘there used to be a plaque on one of the parapets which stated “This bridge was erected with stone at ye equal charge of the County of Denbigh and ye Hundred of Oswestry in ye County of Salop A.D. 1718.”’.

The Industrial Revolution created a need to transport heavy loads of raw materials and finished goods over longer distances. Parish-maintained roads rapidly became even more inadequate. The solution to this new transport problem was the creation of Turnpike Trusts. By means of an Act of Parliament a Trust could be set up, usually with local landowners as trustees, with the power to raise capital, improve roads and demand tolls for passage. Although this was not an original idea – the first Act was passed in 1663 – they did not become widespread, particularly in Wales, until the late 18th century and they continued to grow in number until the middle of 19th century.

Improvements to roads necessitated improvements to the crossings of rivers and streams. An Act of Parliament, The Bridges Act 1530, was passed with the intention of ensuring the regular maintenance of bridges; the justices of the peace of each county were empowered to levy taxes to pay for bridge maintenance: any bridge built on a public road and used by the public became a county road. Presumably this was seen as being sufficient until the greater demands placed on existing bridges by the rapid development of the road network. It was augmented by the Bridges Act 1803 which gave statutory weight to the role of County Surveyor who was responsible for the upkeep of bridges and the roads over them and accountable to the justices of the peace at their Quarter Sessions. Only bridges meeting the county surveyor’s standard were to be maintained by the county. With this permissive legislation in place, it is no surprise that different county authorities adopted differing approaches. Christopher Chalkin wrote that ‘the decision to appoint a surveyor followed usually from a conviction that they (the justices) were at the mercy of workmen where charges and the quality of materials were concerned. Money would also be saved if bridges were regularly inspected and by repairs being done on many occasions while damage was still slight’ (English Counties and Public Building 1650-1830. The Hambledon Press. 1998. p70). The result was that ‘the early nineteenth century bridge surveyors had to inspect periodically the growing number of county bridges, attend sessions and report about them, prepare plans and estimates and superintend all work’ (Chalkin op cit p73). The surveyor would advertise for and select building contractors.

County surveyors additionally would be responsible for other building works such as gaols and shire halls which, in the years they were built, would have consumed a greater share of county financial resources than bridge work.

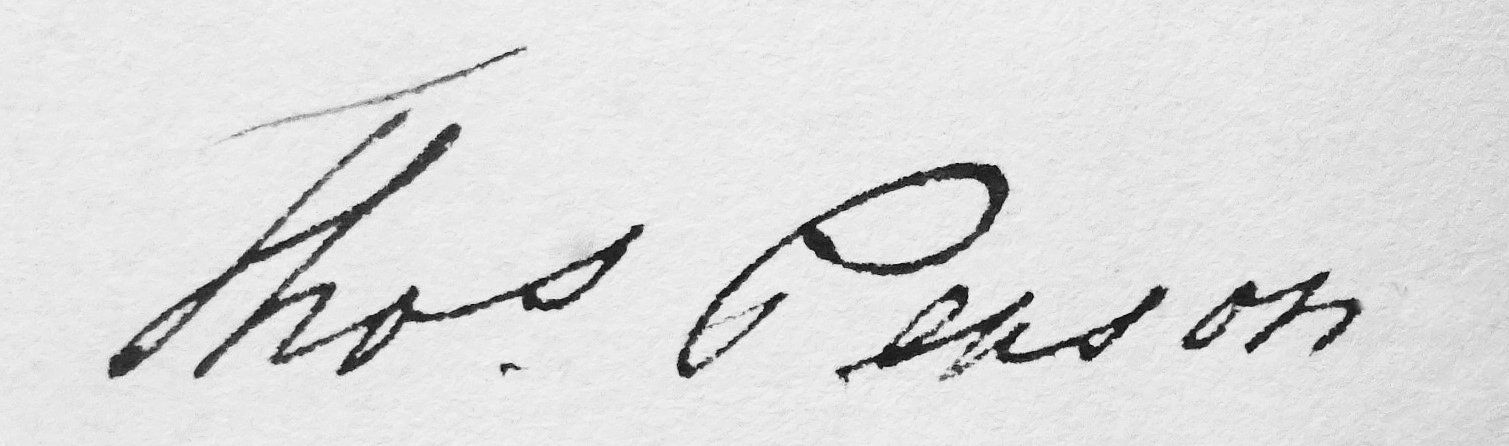

Thomas Penson designed many bridges during his long career as county surveyor of Montgomeryshire and Denbighshire. C Robert Anthony identified 62 in Montgomeryshire in his article ‘ Penson’s Progress: the work of a Nineteenth-Century County Surveyor’ (Montgomeryshire Collections 83 (1995) pp115-175), including some which had been built in Denbighshire but are now in Montgomeryshire as a result of local government boundary changes. Further ones were built in Denbighshire but it seems that the bulk of Penson’s bridge work there involved the maintenance and improvement of pre-existing bridges. Denbighshire appears to have a much greater proportion of 18th century and earlier bridges than Montgomeryshire. This may be a reflection of the reputation Montgomeryshire had in earlier times for the poor state of its roads – Penson had much more bridge building to do in the county. Most bridges were built of stone, a few of iron. The great majority are still in use today, though many have been modified, some extensively. Some have been demolished to make way for newer structures. The descriptions here of most of the extant bridges, rely heavily on Anthony’s researches.

Text: David Ward